JFK & Hemingway: Beyond “Grace Under Pressure”

- Debbie Kim P-B-Kennedy

- Dec 19, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 19, 2021

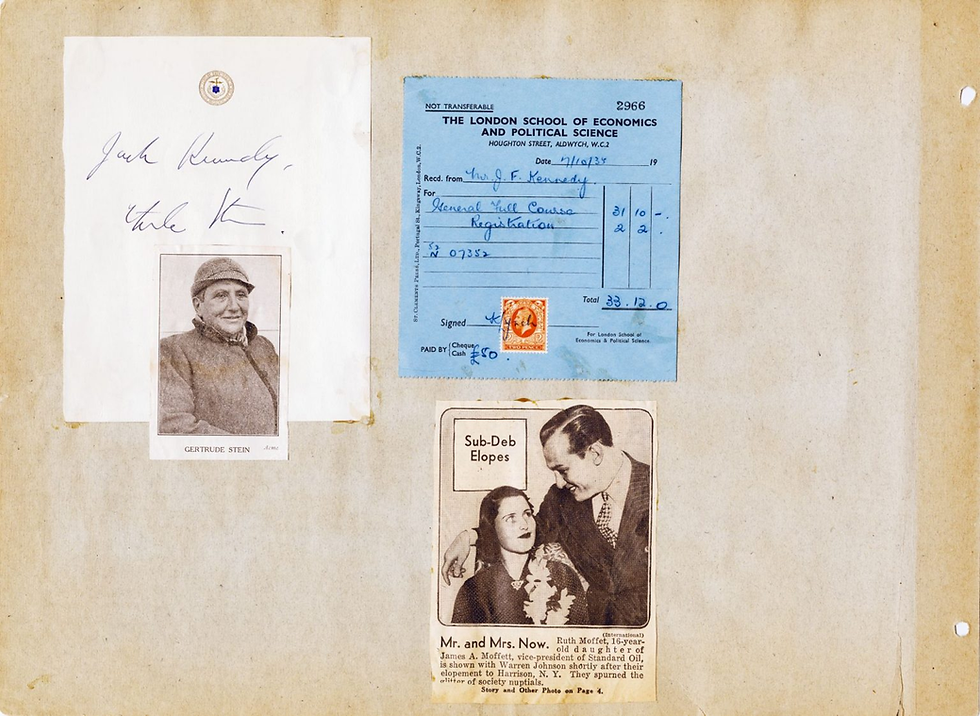

KFC-053-032. Page from John F. Kennedy’s Choate School scrapbook featuring an autograph by Gertrude Stein. Kennedy Family Collection, Box 53, Scrapbooks, and albums: Choate School. ©John F. Kennedy Library Foundation.

By Stacey Flores Chandler, Reference Archivist

When archivists talk with the public about Presidential Libraries, people can often guess the kinds of papers we preserve: those of the President, his Cabinet and other administration officials, his constituents and contemporaries, and even some of his family members. Here at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, most of the 23 million pages in our archives do fall into those categories. But we also take care of a collection that doesn’t quite seem to fit in: the Ernest Hemingway Personal Papers. It’s a fun fact that generates some of our most frequently asked questions: what is the connection between John F. Kennedy and Ernest Hemingway, and how did a Presidential Library wind up with the papers of one of twentieth-century America’s most famous writers?

Archivists haven’t found evidence that John F. Kennedy and Ernest Hemingway met in person, but their interests and networks often overlapped. Born roughly 18 years apart, they both worked as journalists, traveled extensively, and served in wars that changed the course of each of their lives. They also enjoyed a few mutual friendships, including long-term associations with William Walton, a journalist, and painter who reported on World War II alongside Hemingway and later served as Kennedy’s Commission on Fine Arts Chairman. Other intersections come in the form of surprising coincidences – like the time a teenaged JFK ran into writer Gertrude Stein, who knew Hemingway in the 1920s (Kennedy managed to get her autograph for his scrapbook!).

Kennedy showed interest in Hemingway‘s writing on several occasions, too. Sometime after returning from his Navy service in World War II, Kennedy drafted an undated document he labeled “Letter to Hemingway.” In the four-page draft (available in full in our digital archives), Kennedy mused about politics, war, and the pressure young people faced to risk their lives in military service, noting that “there is no comparable pressure on the politician to sacrifice all for the public good.”

JFKPP-039-002-p0027. John F. Kennedy Personal Papers, Box 39.

FKPP-039-002-p0033. John F. Kennedy Personal Papers, Box 39.

Though archivists don’t think Kennedy ever sent a letter like this to Hemingway, we know that he wrote to the author directly at least once. In 1955, then-Senator Kennedy wrote that he’d heard Hemingway’s definition of courage – “grace under pressure” – and hoped to use the quotation in his own book, a work-in-progress called Profiles in Courage. Kennedy asked if Hemingway could tell him the source of the phrase and verify his authorship of it.

JFKPP-031-014-p0014. Carbon copy of John F. Kennedy’s letter to Ernest Hemingway, July 1955. John F. Kennedy Personal Papers, Box 31, Correspondence: Item 2- Harper & Brother, publishers; chronological, 1955: 28 January-31 October.

The response came from Hemingway’s publishers at Charles Scribner’s Sons; they couldn’t verify the quote. With just a few months before the book was set to publish, Kennedy’s own editor, Evan Thomas of Harper & Brothers, discovered the source: Hemingway had used the phrase during a 1929 interview with Dorothy Parker for the New Yorker. With the quote’s origin confirmed, Kennedy included it in the opening lines of his book.

The Hemingway and Kennedy worlds collided again in January 1961, when the writer was included on the list of 168 artists invited to Kennedy’s inauguration. Hemingway kept Kennedy’s invitation for his files, and responded that while his health made it impossible for him to attend, he and his wife Mary wished the administration “all success in their cultural projects and in all things.”

EHPP-IC20-013-p0002 and EHPP-IC20-013-p0003. Ernest Hemingway’s telegram invitation to John F. Kennedy’s Presidential Inauguration, January 1961. Ernest Hemingway Personal Papers, Box IC20, Kennedy, John F.

Meanwhile, Inaugural Committee member Kay Halle was working on a surprise for the incoming First Family: a scrapbook filled with congratulatory messages from American writers, artists, and cultural leaders. An acquaintance of both the Kennedy and Hemingway families, Halle asked Hemingway for a written message shortly after Kennedy’s inaugural ceremonies. He responded with a brief paragraph that included his observations of the day:

Watching the inauguration from Rochester there was the happiness and the hope and the pride and how beautiful we thought Mrs. Kennedy was and then how deeply moving the inaugural address was. Watching on the screen I was sure our President would stand any of the heat to come as he had taken the cold of that day. Each day since I have renewed my faith and tried to understand the practical difficulties of governing he must face as they arrive and admire the true courage he brings to them. It is a good thing to have a brave man as our President in times as tough as these are for our country and the world.

Halle later recalled that Hemingway’s message stood out to the President; while paging through the notes from artists including EB White, Charles and Ray Eames, and Tennessee Williams, Kennedy “stopped at the inscription that Ernest Hemingway had written and read it aloud.” But both Halle and Mary Hemingway noted that Hemingway had trouble writing his tribute; his health was steadily declining and the electric shock therapy he’d been undergoing as a treatment for depression affected his memory and writing ability. On July 2, 1961, Hemingway died by suicide at his home in Idaho, and the White House released a statement about his life and work.

JFKWHSFPS-092-015-p0001. White House statement on the death of Ernest Hemingway, July 2 1961. White House Staff Files of Pierre Salinger, Box 92, John F. Kennedy: Final copies: 2 July 1961.

At the time of Hemingway’s death, much of his literary estate (including drafts of his most famous works) remained at his home in Cuba, the Finca Vigia. The Hemingways hadn’t visited the Finca since the late 1950s, and relations between the United States and Cuba had continued to deteriorate after Kennedy’s failed Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961. Traveling to the island became difficult for Americans and created an urgent problem for Mary, who later explained that her husband had hoped to make his papers available for study. But William Walton, as an old friend of both Kennedy and Hemingway, was uniquely positioned to help; he convinced the Kennedy administration to help Mary enter Cuba, and she was soon on her way.

PX94-2:022. David Finley, President John F. Kennedy, and William Walton at the White House. Photographer unknown. William Walton Personal Papers, Box 1, Letters from Kennedys.

In Cuba, Mary agreed to donate the Finca Vigia to the Cuban people in exchange for Fidel Castro’s permission to bring Hemingway’s papers back to the United States. Walton later noted that the President was impressed with Mary’s political savvy: “He was just delighted when I came down to the White House and told him what she had done in leaving the Finca to the Cuban people, not to the Castro government. And the President just clapped his hands and said, ‘Oh, I couldn’t have done it better myself.’” Soon after, Kennedy invited Mary to sit next to him at a dinner for Nobel Prize winners at the White House, where actor Frederic March performed a reading of Hemingway’s unpublished work

Just a few years later, Jacqueline Kennedy found herself making plans for her own late husband’s archives. William Walton encouraged Mary to donate Hemingway’s materials to the planned John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in recognition of the Kennedy administration’s help retrieving the papers from Cuba, as well as the Kennedys’ interest in promoting the arts. Mary, who noted in her oral history that her husband had been “a fervent and profound admirer” of the late President, connected with Jacqueline Kennedy and offered to donate the collection in 1968. Since then, the Library has welcomed many additional Hemingway-related collections into our archives, along with thousands of researchers and Hemingway fans eager to explore them. Archivists are often asked about the surprising presence of these collections among the government materials that are more typical of a Presidential Library, and we’re fortunate to help preserve them and make them available to all.

See the complete guide to the Ernest Hemingway Personal Papers and the Ernest Hemingway Photographs, or explore related collections and media galleries. All are welcome to visit the archives; email a Reference Archivist at Kennedy.Library@nara.gov to make an appointment!

COURTESY OF JFK LIBRARY - USE THE FOLLOWING LINK -

OR AS STATED ABOVE -

email a Reference Archivist at

to make an appointment!

ALL THIS IS COPIED FROM THE JFK LIBRARY.

TYPED BY: DEBORAH KIM BOUVIER-KENNEDY

THE YOUNGEST BIO-DAUGHTER OF U.S. PRESIDENT JOHN "JACK" F. KENNEDY

12/19/2021

DEBORAH "DEBBIE" KIM - BORN CLASSIFIED JULY 29, 1964 IN NEW YORK -

HAS ALSO BEEN KNOWN BY THE LAST NAMES OF -

GUFFEY, GARNER, COLVER, HICKS

OR ABBREVIATED AS -

B-, G-, C-, H-, K-

Comments